TL;DR. Context engineering means giving an AI system—usually a large language model (LLM)—all the instructions, data, examples, tools, and history it needs to plausibly solve a task. It’s the evolution of classic prompt engineering into a broader, system-level discipline.

The shorter version: the quality of the model’s output is bounded by the quality of the context you feed it.

How to Improve Your AI Prompts Right Now

To get good results from an AI, you must give it clear, specific, and relevant context. Vague inputs lead to vague answers; missing inputs lead to hallucinations.

Here are five fast ways to level up your prompts:

Be precise about the task and constraints.

State exactly what you want, how long it should be, what format it should follow (JSON, Markdown, diff, etc.), which libraries or patterns to use, and what to avoid.Attach the right artifacts.

For coding work, include the actual files or snippets involved, not just a description. Add relevant design doc sections, database schemas, and even pull request comments that show how your team thinks about the code.Include runtime evidence.

When debugging, paste full error messages, stack traces, or failing test output. The critical clue is usually in the logs, not in your summary of the problem.Show examples of the output you want.

Provide one or two high-quality examples: a formatted API response, a well-documented function, a perfect migration script. Few-shot examples give the model a concrete pattern to imitate.Cut everything that isn’t relevant.

More context is not always better. Irrelevant files, entire logs, or giant documents can distract the model and degrade performance. Aim for focused context, not maximal context.

Everything else in this article is about turning these instincts into a disciplined practice: context engineering.

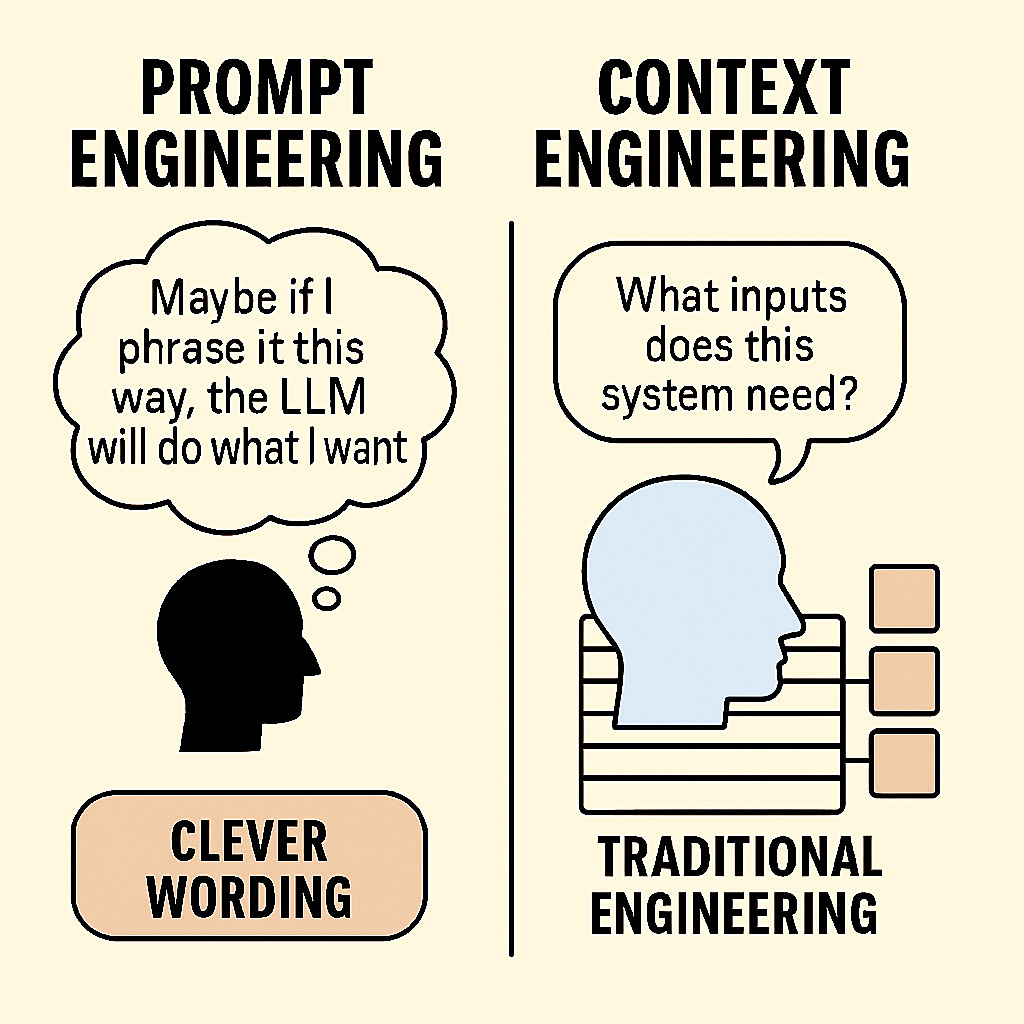

From “Prompt Engineering” to “Context Engineering”

Prompt engineering became a buzzword for the craft of phrasing inputs to get better outputs from LLMs. We learned to “program in prose” with magic-sounding lines like “You are an expert X, think step-by-step…”

Outside the AI community, this often got oversimplified into “type something fancy into a chatbot and hope for the best.” The term never quite captured what serious practitioners were actually doing.

As real applications grew more complex, the limits of focusing on a single prompt became obvious. A witty one-off prompt might win a demo, but it doesn’t power a reliable IDE assistant, support bot, or research agent.

That’s why the field is converging on context engineering as a better label. Instead of obsessing over one sentence, we design the entire context window the LLM sees:

- Instructions and role

- Domain knowledge and documents

- Tools and external results

- Conversation history and state

- Examples and formatting expectations

The term was popularized by developers like Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke and AI researcher Andrej Karpathy in mid‑2025.

“I really like the term ‘context engineering’ over prompt engineering,” wrote Tobi. “It describes the core skill better: the art of providing all the context for the task to be plausibly solvable by the LLM.”

Karpathy agreed, noting that people hear “prompt” and think “short instruction,” while real LLM apps are about the delicate art and science of filling the context window with exactly the right information at each step.

If prompt engineering was about writing a magic sentence, context engineering is closer to writing the entire screenplay the model will act out.

- Prompt engineering ends when you craft a good instruction.

- Context engineering begins with designing systems that assemble and update context from memory, tools, and data in a structured way.

In other words, robust LLM apps don’t succeed by luck. They succeed because someone carefully engineered the information environment the model operates in.

What Exactly Is Context Engineering?

At its core, context engineering means dynamically giving an AI everything it needs to succeed—at runtime.

That includes:

- Clear instructions and role

- Relevant data and documents

- Helpful examples

- Access to tools and their results

- Summaries of prior history or state

All of this is assembled into the model’s input for a given call.

A mental model (popularized by Karpathy and others) is helpful here:

- Treat the LLM like a CPU.

- Treat the context window (the text input) like RAM or working memory.

- Treat yourself (or your app) like the operating system that decides what code and data to load into memory.

Your job as a context engineer is to fill that working memory with just the right information, at the right time, in the right format.

In practice, that means several things.

It’s a system, not a one-off prompt

In a well-designed app, the “prompt” the model sees is a composition of different pieces:

- A system or role instruction written by the developer

- The latest user query

- Retrieved snippets from code, docs, or knowledge bases

- Tool outputs like search results, SQL query results, or test logs

- A few examples of the desired output format

All of that is woven together programmatically.

Imagine a coding assistant that gets, “How do I fix this authentication bug?” Behind the scenes, the system might:

- Search your repo for relevant auth code

- Pull in the failing test and error logs

- Build an input like:

You are an expert coding assistant.

The user is facing an authentication bug.

Relevant code snippets:

[...code here...]

Error log:

[...logs here...]

Task: Propose a minimal, safe fix. Explain your reasoning first, then show a patch diff.

The user never sees this full prompt, but the model does. Context engineering is the logic that decides what to pull in and how to stitch it together.

It’s dynamic and situation‑specific

Unlike a static prompt copied from a blog post, context assembly happens per request.

The system might:

- Include different files or docs depending on the query

- Summarize prior turns in a long chat instead of repeating them verbatim

- Fetch a design spec from your wiki when the user mentions “the design doc”

- Add PR feedback when the user references “the last review comments”

The context changes as the state changes. That dynamism is not optional—it’s exactly what lets LLMs handle complex, multi-step work.

It blends different kinds of information

Libraries like LangChain break context into at least three facets:

- Instructional context – system prompts, guidelines, and few-shot examples

- Knowledge context – facts, documents, and domain material, often pulled in via retrieval

- Tools context – outputs from external tools or APIs, like search results, code execution, or DB queries

Serious LLM apps tend to need all three:

- Instructions to define what to do

- Knowledge to answer correctly

- Tools to interact with the outside world

Context engineering is the discipline of managing these streams and merging them into a coherent whole.

Format and clarity matter as much as content

It’s not just what context you supply—it’s how you package it.

Dumping a giant blob of unstructured text into the prompt is like sending someone a 200‑page PDF and saying “answer this email.” The information might be in there, but good luck finding it.

Effective context engineering involves:

- Summarizing long content down to the essentials

- Using headings, bullet points, or sections to highlight what matters

- Labeling parts of the input (“User query:”, “Relevant schema:”) so the model can parse roles

- Choosing helpful formats (code blocks, JSON, tables) when they aid understanding

For example, instead of pasting a 300‑line stack trace, you might include:

Test failure (last 10 lines):

[...key lines here...]

You’re not hiding information; you’re curating it.

Above all, it’s about setting the model up for success

An LLM is powerful, but it’s not psychic. It only has:

- What you put into the context window

- What it picked up during training

If it fails or hallucinates, the root cause is often that we:

- Didn’t give it the right context, or

- Gave it poorly structured context

When an “agent” misbehaves, it’s usually because “the appropriate context, instructions and tools have not been communicated to the model.”

Garbage context in, garbage answers out.

Conversely, when you supply relevant, clearly structured information, performance jumps—sometimes dramatically.

Feeding High‑Quality Context: Practical Techniques

So how do you turn this into a concrete practice instead of a vague ideal? Here are core techniques that show up again and again in strong LLM apps.

- Include the actual source code and data.

- Be explicit in your instructions.

- Show working examples of the target output.

- Inject external knowledge when needed.

- Always include logs and error messages when debugging.

- Carry conversation history, but do it smartly.

The golden rule: LLMs are powerful, but not mind‑readers. Too little context and they guess. Too much irrelevant context and they get distracted or confused. Your job is to feed them exactly what they need—and nothing they don’t.

Addressing the Skeptics

Many developers roll their eyes at “context engineering.” To them, it sounds like rebranded prompt engineering or, worse, a fresh layer of hype on an already buzzy field.

That skepticism is understandable.

Traditional prompt engineering focused on instructions: how to phrase questions, how to set roles, how to coax chain-of-thought reasoning. Useful, yes—but narrow.

Context engineering widens the scope. It covers:

- Dynamic data retrieval and knowledge integration

- Memory and state management across long sessions

- Tool orchestration and environment control

- Careful handling of multi‑turn interactions

And yet, the critics are still right about something important: a lot of current AI practice lacks the rigor we expect in real engineering.

There’s too much trial-and-error, not enough systematic measurement, and often a shaky understanding of failure modes. Even with perfect context engineering, LLMs still hallucinate, make logical errors, and struggle with complex reasoning.

So let’s be honest:

- Context engineering is not a silver bullet.

- It is a way to reduce damage and extract more value within today’s limits.

Think of it less as magic and more as optimization and risk management.

The Art and Science of Effective Context

Great context engineering strikes a balance: give the model everything it truly needs, and ruthlessly cut what it doesn’t.

Karpathy called context engineering a mix of science and art. Both sides matter.

The “science” side

The scientific side is about principles, techniques, and constraints we understand fairly well:

- If you want good code generation, include the relevant code and error messages.

- If you want good question answering, retrieve supporting documents and attach them.

- If you want consistent style, show examples in the desired style.

We also have proven methods:

- Few-shot prompting – teaching by example within the prompt

- Retrieval‑augmented generation (RAG) – fetching knowledge and injecting it into context

- Chain‑of‑thought prompting – asking the model to reason step by step

On top of that, every model has hard limits: context length, latency, and cost. Overstuffing the context window can:

- Increase latency and token cost

- Push important details off the edge of the window

- Even degrade answer quality by burying key facts in noise

Karpathy summarized it neatly:

“Too little or of the wrong form and the LLM doesn’t have the right context for optimal performance. Too much or too irrelevant and the LLM costs might go up and performance might come down.”

So the science is in selecting, pruning, and formatting context:

- Use embeddings to retrieve only the most relevant documents.

- Summarize long histories into compact “state of the world” snippets.

- Watch for failure modes like context poisoning (bad content lingering in history) and distraction (too many tangents).

The “art” side

Then there’s the art: the intuition you develop by living with a model.

Over time, you notice quirks:

- One model performs better if you begin with a short outline of the approach.

- Another misinterprets a common domain term, so you pre‑define it in the context.

- A particular formatting (like pseudo‑code or tabular data) helps a given model stay on track.

These aren’t in any official manual; you learn them by experimentation and by reading others’ post‑mortems.

Classic prompt‑crafting lives here: phrasing, ordering, and shaping how the model “thinks aloud.” The difference now is that this craft is in service of a larger system that includes retrieval, tools, and memory.

Common patterns context engineers lean on

A few recurring strategies show up in many strong systems:

Retrieval of relevant knowledge.

RAG pipelines search over docs, wikis, or code to fetch chunks that match the user’s query. These snippets go into the prompt right before the question. The goal is to ground the model in real, up‑to‑date facts and drastically reduce hallucinations.

Few‑shot examples and role instructions.

You set the persona (“You are an expert Python developer…”) and show a couple of high-quality input/output pairs. The model then generalizes the pattern. Here, prompt engineering becomes a subset of context engineering.

Managing state and memory.

Conversations and tasks can span hundreds of turns. Since context windows are limited, you:

- Summarize earlier turns into shorter notes

- Persist key facts to an external store

- Retrieve them later when needed

Systems like Anthropic’s Claude already auto‑summarize long chats to stay within limits. Advanced agent frameworks even let models create “notes to self” that are stored and later recalled.

Tool use and environmental context.

Modern agents can call tools: run code, hit APIs, browse the web, query databases. Each tool call produces new context:

- The model decides which tool to use.

- Your system executes it.

- You feed the tool’s output back into the next prompt.

A lot of agent frameworks (LangChain and similar) are really context orchestration layers around tool calls.

Information formatting and packaging.

You often have more raw information than you can realistically fit. So you choose:

- Which parts to show fully

- Which to compress into summaries

- Which to expose as structured fields rather than blobs

Think like a UX designer—but your “user” is the LLM.

When you see an LLM apparently “reasoning” through a complex, multi‑step process—debugging, refactoring, planning—you’re usually seeing the tip of an iceberg of context engineering underneath.

The Challenge of Context Rot

As we get better at assembling rich context, a new problem appears: context can poison itself over time.

Developer Workaccount2 on Hacker News coined the term “context rot” for this phenomenon: context quality degrades as conversations grow longer and accumulate:

- Failed attempts

- Dead ends

- Contradictory drafts

- Tangential explorations

The pattern is familiar:

- You start with crisp instructions and minimal, relevant context.

- The AI performs well for a while.

- The session grows: more tries, more logs, more partial fixes.

- Responses slowly become worse—more confused, more off-topic, more hallucinated.

Why? Because the context window is the model’s working memory. Filling it with old drafts and mistakes is like trying to write clean code on a desk piled with outdated printouts.

The model:

- Struggles to distinguish “current truth” from “historical noise.”

- May anchor on earlier wrong outputs and compound them.

- Gets distracted by tangents that are no longer relevant.

This is especially painful in exactly the workflows LLMs are great for: debugging, refactoring, multi‑day research, large document edits.

To manage context rot, you need deliberate information hygiene.

Practical strategies:

Context pruning and refresh.

Periodically summarize what matters and start a fresh session seeded only with that summary. Think of it as garbage collection for your prompt.Structured context boundaries.

Use explicit markers like “Previous attempts (for reference only)” versus “Current working solution.” This signals to the model what to prioritize.Progressive context refinement.

After major progress, rebuild the context from scratch. Extract the final decisions, current state, and successful snippets, and drop the rest.Checkpoint summaries.

At regular intervals, ask the model to summarize what’s been achieved and what remains. Use these checkpoint summaries to seed new sessions.Context windowing.

Break very long tasks into phases with clear boundaries. Each phase gets a clean context that includes only the essentials from the previous phase.

The deeper lesson: “Just dump everything into the prompt” is not a strategy. Good context engineering includes deciding what to exclude or compress, not just what to add.

Where Context Engineering Fits in Real LLM Systems

Context engineering is central, but it’s only one part of the stack needed for production‑grade LLM applications.

Karpathy calls it “one small piece of an emerging thick layer of non‑trivial software” that sits between users and models. Around context, you still need quite a bit of architecture.

A real system often includes:

Problem decomposition and control flow.

Instead of treating a user request as a single monolithic prompt, robust systems break it into steps. For example: first ask the model to outline a plan, then execute each step with its own context. You design a kind of “workflow script” whose functions are LLM calls plus tool calls.

Model selection and routing.

You might use different models for different jobs: a small, cheap one for quick classifications; a larger one for final answers; a code‑tuned model for programming tasks. Each has its own context limits and quirks. Your orchestration layer decides which model to call and how to adapt the context to fit.

Tool integrations and external actions.

If the AI can hit APIs, run code, or query databases, your app must manage those capabilities: expose tools to the model, execute calls safely, and feed results back as context. This often creates a loop: prompt → tool → new context → prompt.

User interaction and UX flows.

Many apps keep a human in the loop. A coding assistant might propose a patch and ask for approval. A writing assistant might offer multiple drafts. The user’s choices must feed back into context (“The user chose option 2 and wants it shorter.”).

Guardrails and safety.

You need filters and policies: content moderation, permission checks, output validation. Sometimes a second model audits the first. These guardrails are themselves often implemented via prompts—extra context that encodes policy and constraints.

Evaluation and monitoring.

You log prompts, contexts, and outputs (with appropriate privacy controls). You measure success rates, latency, failure patterns. When something goes wrong, you inspect the exact context the model saw and adjust your pipelines.

Put together, this looks less like a simple script and more like a new application architecture. Your “business logic” is now:

- Managing information flows (context)

- Orchestrating AI calls and tools

- Keeping a human in the loop when necessary

Within that architecture, context engineering sits at the heart. If you can’t get the right information into the model at the right time, nothing else will reliably fix your system.

Conclusion: Think in Context, Not Just Prompts

By mastering how you assemble complete, focused context—and coupling that with systematic testing—you dramatically increase your chances of getting useful, reliable output from AI models.

For experienced engineers, this isn’t entirely new. It’s old principles in a new setting:

Garbage in, garbage out.

Now it shows up as “bad context in, bad answers out,” so you invest more effort in input quality.Modularity and abstraction.

You describe tasks, give examples, and let AI handle details, while orchestrating pipelines of tools and model calls.Testing and iteration.

You write evals, inspect failures, and refine prompts and retrieval logic the way you’d profile and refactor code.

Adopting a context‑centric mindset means accepting responsibility for what the AI does. The model isn’t an oracle; it’s a component you configure and drive with data, rules, and constraints.

Here are concrete ways to bring context engineering into your daily work:

Invest in data and knowledge pipelines.

Build the retrieval layer: vector search over docs, access to the codebase, links to style guides, API specs, and schemas. Most of the value you’ll unlock comes from the external knowledge you can inject.

Develop prompt templates and libraries.

Instead of ad‑hoc prompts, create reusable templates like “answer with citations,” “propose a code diff given an error,” or “summarize a design doc for executives.” Version them, document them, and treat them like shared utilities.

Use tools and frameworks that expose the guts.

Avoid opaque “just give us a prompt” solutions when you need reliability. Favor libraries or custom orchestration where you control retrieval, formatting, tool calls, and safety layers. Visibility into context assembly makes debugging possible.

Monitor and instrument everything.

Log model inputs, assembled context, and outputs (within privacy limits). Use tracing tools to see how each prompt was built. When you see a bad answer, inspect the context. Did something crucial get left out? Was something misleading included?

Keep the user in the loop.

Give users ways to add more context: attach files, highlight relevant code, choose which document sections matter. Let them correct AI mistakes and feed those corrections back into future context.

Train your team in context thinking.

Treat prompts and context pipelines as first‑class citizens in code reviews. Ask, “Is this retrieval grabbing the right docs?” “Is this prompt clear enough?” Share lessons and weird failure cases so everyone learns faster.

Over time, context engineering will feel as normal as writing SQL or designing REST APIs. “Did you set up the context correctly?” will become a standard review question.

One actionable next step: pick a single workflow you already have—like “debug a failing test” or “summarize a PR”—and sketch the ideal context pipeline for it. Decide what artifacts to retrieve, how to format them, and how to trim noise. Implement that, and measure the improvement.

Those who learn to feed AI systems the right context will always get more out of them than those who just type clever prompts.

Happy context‑coding.